The exhibition ‘Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art‘ is showing at Tate Modern, London until 14 October 2018. It charts photography’s role in twentieth and twenty-first century efforts to explore abstract art but it does it in a rather staid, historical/academic – and expensive – way that gave no clue about the sense of play involved in creating abstract art. Nevertheless it is a good synopsis show that achieves what it ‘says on the tin’.

Even the staff get to appreciate the art sometimes, though the first 10 rooms of unremitting black & white images did start to get dreary (never thought I’d say that about b&w photos, but there it is).

This exhibition is a journey through photographic abstraction from the early twentieth century to the present. It demonstrates relationships between different photographers and different media, with the occasional painting and sculpture added to the mix. Most of the exhibition is a steady progression through varying approaches to abstraction. When you consider that the primary use of a camera is to record what’s in front of it, using a camera to make abstract photos is fighting the natural characteristics of the medium. In this exhibition we see the world presented from bizarre viewpoints, the use of long focal length lenses to compress perspective and close-ups to distort scale. We also find photographic materials used outside the camera to record the action of light, and even invisible radiation, directly. The first ten of the twelve rooms are almost entirely black & white prints. I hate to say this as a black & white enthusiast, but ten rooms of black & white abstracts did start to become kinda’ boring. But then finally as we approach the 21st century colour starts to happen. Hurrah! It starts as a dark blue whisper of large format Polaroid prints then finally, finally bursts into the exuberance that can be abstract art. It’s true that colour film wasn’t available in the early 20th century and unfortunately there was an almost universal attitude that serious photographers only made black & white images – and what a missed opportunity that was! Rooms 11 and 12 of the exhibition seem to conflate colour film and digital technology as a single giant leap away from photographers worthily pursuing abstraction to artists playing with photographic means to create abstract art. With the depth of analysis given in the first ten rooms it felt like the final two rooms were rather rushed and cramped, not in their physical space, which was large, but in their balance compared with the previous part of the show. I feel this is a missed chance to show more of the diverse abstract photography being produced in the last three decades, and the show under-represented the possibilities digital technology has brought to the arena. I swung from feeling turned off by too much black & white imagery to wanting ‘more! more!’ of the latest works.

Broadly the exhibition was organised chronologically, though thankfully not too strictly, and each room had a contextualising statement that could be read or ignored as you please. Although there are well known images by photographic ‘names’ it was good to see these balanced with less well known equals. It was also good to see a sprinkling of Japanese photographers in with the predominant European and American names.

Abstract art is viewed by some people like wallpaper: decorative but shallow in meaning, and using photography to create abstracts can tempt the viewer into trying to work out what it was in front of the camera. The first approach has a lack of engagement, the second is engaged but missing the point. There is a relevant quote buried in this exhibition: when commenting on the title of a proposed abstract photography exhibition in the late 1950’s Minor White wrote to the curator ‘…I think that “towards abstraction” is a dead end for photographers to follow – whereas “towards revelation” is towards life itself.’ [letter from Minor White to Grace Mayer. 1959]. As Minor White implies, abstract images require engagement by the viewer as well as the photographer and without this willingness to engage imaginatively, emotionally and intellectually, this exhibition would be an overpriced expensive waste of your time. But if you want a good assembly of abstract photography set in an historical context, take a deep breath and shell out the £20.

I wouldn’t consider any exhibition worthwhile without discovering a few delights, and this show didn’t disappoint me. A few of my memorable images are:

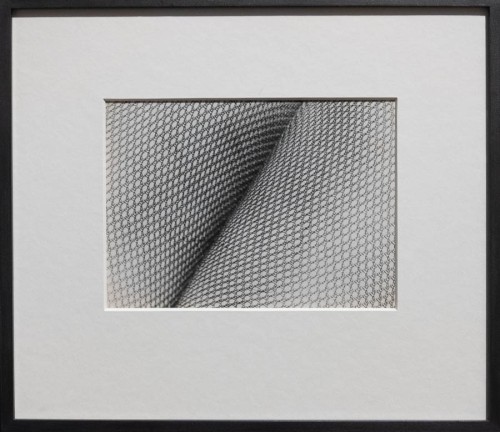

Iwato Yamawaki’s image caught my eye not just for its own quality but for the similarity to ‘Tights‘ (c.2011) by Daido Moriyama. Given the dates it is easy to imagine that Moriyama could have been inspired by Yamawaki.

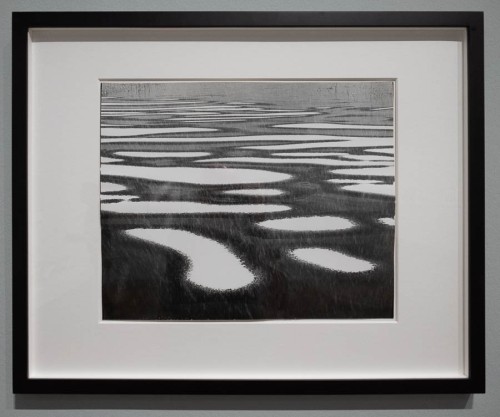

Peter Keetman has an eclectic eye for the abstract image but this one particularly caught my eye. It is on the cusp between reality and unreality, and I think it is this that gives it so many possibilities for the imagination. Is it a landscape? Or perhaps a photomicrograph? Or something else entirely? Unusually for an abstract, it has a strong sense of perspective.

I’ve been wanting to see this work by Anthony Cairns since I read about it last year. The images have a hint of the quality of old tintypes about them: quite dark and melancholic, as if uncertain whether to be a negative or a positive. They are an abstraction of reality (but aren’t all photographs?) ‘though anchored in reality so not fully abstract, but definitely worthy of a place in this show. I like the way the multiple shadows caused by refraction through the acrylic mounts gives the images another dimension too.