The Photographers’ Gallery, London UK, is currently exhibiting work by the four short-listed nominees for this year’s Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation prize (until 12 June 2022). Each has a different approach and each would be a worthy winner. It is easy to pick a personal favorite but much harder to say which photographer is the most worthy based on the exhibited work. Their back story and full body of work will need to be taken into account before a winner emerges.

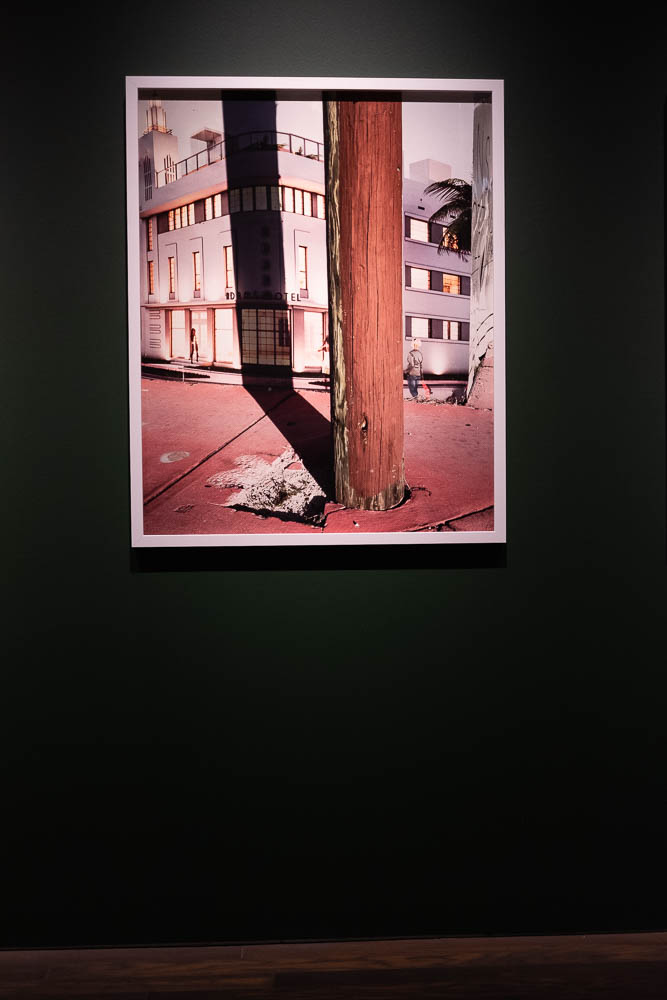

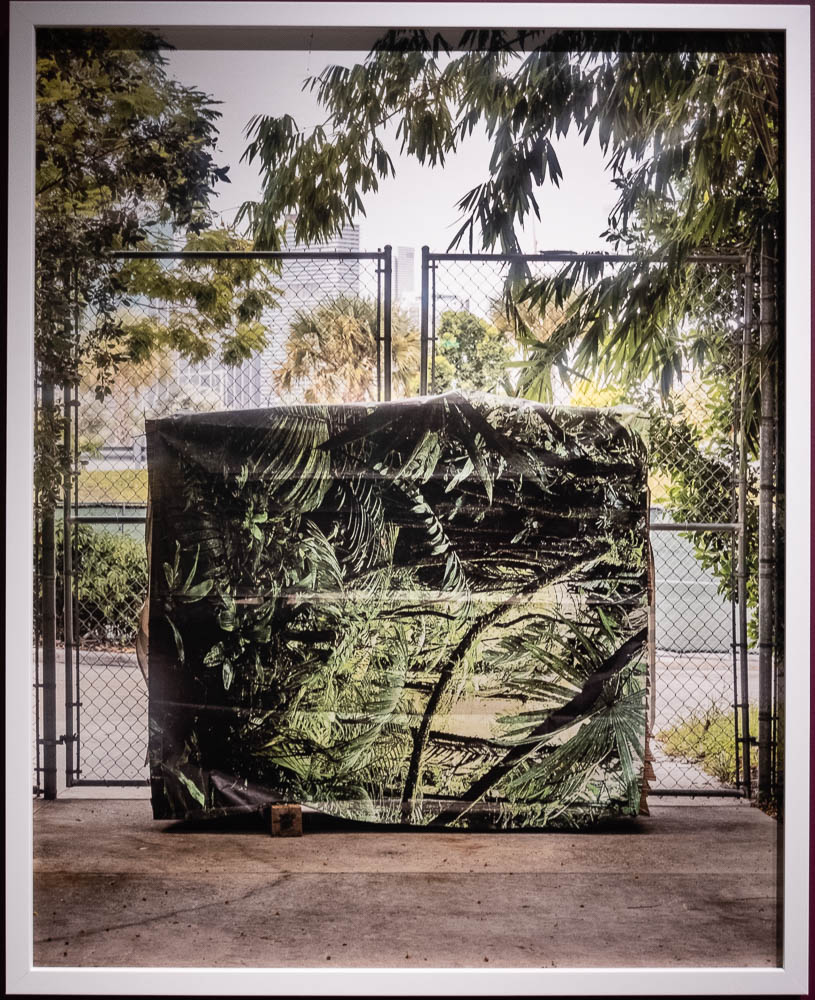

Anastasia Samoylova ‘Floodzone’

Anastasia’s work is a climate change inspired on-going project examining the dissonance between continued habitation of coastal settlements and the rise in sea level. Her project started in Miami, Florida but is spreading to other communities. Many of her images seem at first glance banal, inconsequential, but you don’t have to look at them for long before their meaning deepens or the image becomes quizzical or disconcerting, which leads in turn to alternative readings.

One approach she uses is the combining of real 3D objects with 2D hoardings:

Anastasia’s approaches are messages to the reader to look with a more questioning attitude at what you see. Ask, for example, what will these scenes look like in 10 or 50 years time?

Jo Ratcliffe ‘Photographs 1980s – Now’

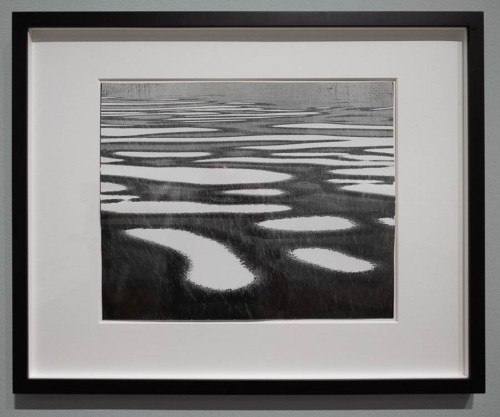

Jo’s photos have been made over a 30 year period and display a remarkable consistency of approach. They depict places of conflict and dispossession in South Africa and Angola though they are not of the conflict itself but the aftermath. They are still, haunting, monochrome images, each speaking of desertion and time suspended as if the clock dare not tick another second.

For the most part the images can be read individually or with a neighbouring image but there is a double-sided concertina book of images taken every 100km along the road from Johannesburg to Cape Town and back. I’m not a fan of this type of mechanistic photography and this book felt cold and uninviting. The rest of the images had a melancholy about them as if a wound had healed but the scar remains. The exhibition is an essay in the need to forgive but not to forget.

Deana Lawson ‘Centropy’

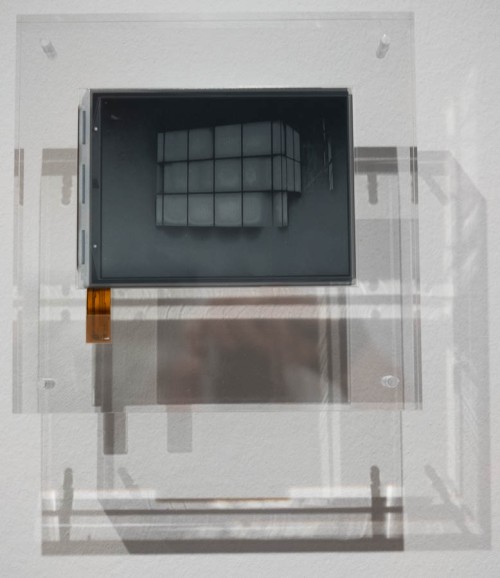

Deana’s photography plays with dichotomies: what is real versus what is unreal, what is shown versus what it means. Her photos can be read individually but when combined, themes of race and nuclear & extended family occur.

The images have mirror frames. This could allude to an Alice Throught the Looking Glass surreality. It also gives the viewer a glimpse of themselves, which creates an interesting engagement. An unintended consequence is reflections on the gallery floor giving an unexpected three dimensionality to the space.

‘Niagara Falls 2018’ is intriguing – it has water apparently flowing in multiple directions and when the image is rotated it takes on a different sense and aquires a new meaning:

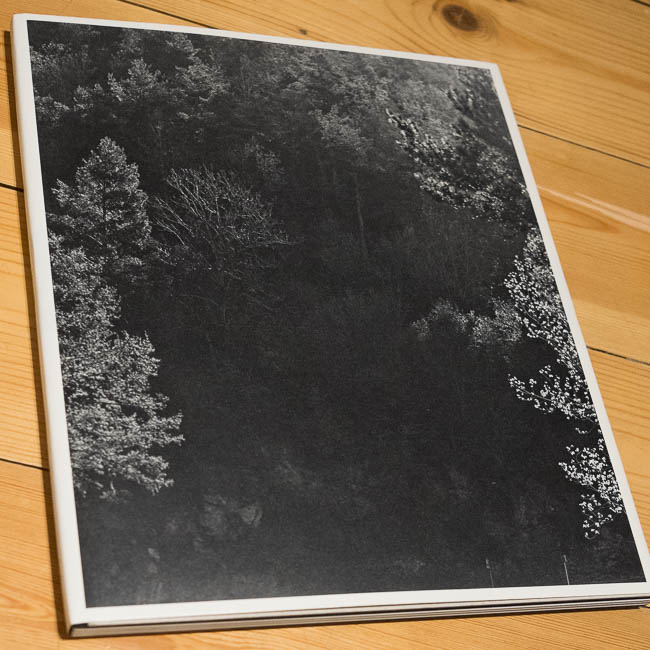

Gilles Peress ‘Whatever You Say, Say Nothing’

Although the photographs were taken as documentary images of the Trouble in 1970s Northern Ireland, this nomination is for a reimagining of the archive which has been published as a book. By grouping images in a fictional timeline or storyline the specificity has been removed from the Northern Ireland context and generalised to the impact of civil strife anywhere. They convey the gritty surreality of life in Northern Ireland at the time but also contain the destructive cycle of time and events repeating themselves with slight variation, seemingly endlessly. The judicious use of words and typography compliments the images very well.

Impressions

All four nominees are worthy of this year’s prize. I generally prefer more recently made work but the use of older images in a new or on-going context is perfectly valid. The photographer I would most like to see more work from is Anastasia Samoylova; she’s exploring a contempoary issue in a variety of ways and if winning this prize helps her to continue this project I hope she wins.